Maxim free download pdf - sorry

Download (PDF) - Maxim Institute

TAX DISCUSSION SERIES: PAPER 3

Lifting the Bucket

Tax policy and economic growth

TAX DISCUSSION SERIES: PAPER 3

Lifting the Bucket:

Tax policy and

economic growth

by Steve Thomas

First web edition published in April 2010 by MaximInstitute

PO Box 49 074, Roskill South, Auckland 1445, New Zealand

Ph (+64) 9 627 3261 | Fax (+64) 9 627 3264 | www.maxim.org.nz

Copyright © 2010 MaximInstitute

ISBN 978-0-9582976-7-7

This publication is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information

retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. No reproduction may be made, whether

by photocopying or by any other means, unless a license has been obtained from the publisher or its agent.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

v

SECTION 1 - Introduction 1

SECTION 2 - Tax system design principles 13

SECTION 3 - Research findings: Growing a prosperous economy 23

SECTION 4 - Research findings: How taxes affect our lives and our prosperity 33

SECTION 5 - Research findings: The link between tax, government spending and prosperity 63

SECTION 6 - Policy recommendations and conclusion 77

APPENDIX - Survey methodology 89

ABOUT THE AUTHOR/ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 91

This page has been

intentionally left blank

for publishing purposes

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

“We contend that for a nation to tax itself into prosperity is like a man standing in a bucket

and trying to lift himself up by the handle.” 1 Winston Churchill

New Zealand is a bit like Churchill’s man in a bucket,

trying vainly to lift himself to greater prosperity

but limiting his chances by the position he adopts.

We need to lift ourselves up, to achieve greater

economic growth, but our current tax policies

reduce our chances of success even as we pull on the

handle. Fortunately, there are ways that we can step

out of the bucket and lift it higher—ways to improve

our tax policies so that growth increases and social

well-being improves.

Economic growth is only one ingredient in a

healthy society, but it is a crucial one. Economic

growth is not an end in itself, rather it serves

good ends, contributing to people’s well-being,

living standards and opportunities in life. Growth

is affected by tax, which is how the government

raises its revenue to do the crucial things we need

it to, like paying for a police force or a public

education system, building roads and supporting

the poorest when they need it.

However, when we try to take too much money

out of the economy in tax to fund government

spending, we risk undermining the very source

of that revenue. Also, if government spending is

misdirected or of poor value, then we hamstring the

economy’s ability to produce what we need and the

amount of tax the government is able to collect.

This relationship between tax and the economy

therefore needs to be carefully considered. We

need to design the tax system so that it allows the

government to take the money it requires, while

doing the least amount of damage to the economy

and so too our potential prosperity.

This paper tackles these issues by asking

questions about how taxes affect economic

growth. It also asks how growth is affected by the

level and make-up of the government spending

that is typically funded by our taxes. It answers

these questions through detailed literature reviews,

summarising the main themes of the reviews in

this report.

Unfortunately, the questions are urgent because

New Zealand’s economic outlook is not good.

Our current spending pattern is unsustainable. If

continued it would see spending climbing everhigher

than revenue and deficits ballooning. 2 Core

government spending is forecast to stay at about

36% of the total amount we produce (GDP) until

2011, when it is expected to drop slightly to between

34% and 35% of GDP over the period 2012-14. 3

That drop would normally be a good sign, but the

bad news is that the amount of money government

collects is expected to also drop from 33% of

GDP in 2009 to about 31% of GDP in 2010—and

stay at about that share throughout the forecast

period to 2014. 4 This means the Government will

be constantly out-spending its income, paying for

expensive programmes like interest-free student

loans and Working for Families tax credits, and

subsidising KiwiRail and KiwiSaver incentives, even

as the economy has weakened. 5 Demographic change

over the next twenty to thirty years—what is often

called a greying population—means there will not

be enough taxpayers or tax revenue to pay for the

kind of government services we receive today, unless

we boost productivity or are prepared to foot the bill

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

v

with higher public debt, higher taxes or both. 6

Problems also abound in the tax system itself.

We rely heavily on personal and corporate income

taxes—the least growth-friendly taxes. Also, tax

bases are mobile, and they are voting with their feet.

For example, Inland Revenue has reported that about

24% of highly-skilled New Zealanders live overseas. 7

There is also a risk of international tax competition,

in which our tax system is compared unfavourably

to that of other countries by firms who are deciding

which countries to base themselves in. An uneven

system, finally, invites tax planning and avoidance—

an invitation which has been accepted.

To continue along with the way things are now is

not an option. These challenges threaten our country’s

long-term well-being. The research we review in this

paper suggests, however, that there is a better way.

This paper is the third in a series that stems from

a very basic question: “What is tax, and what is it

for?” and that seeks to join up theory about the role

of government and community, the meaning and

enacting of justice, compassion and freedom, and

the economic literature on taxation. The goal of the

series is concrete policy recommendations based on

this holistic framework.

TAX SYSTEM DESIGN PRINCIPLES

To provide a framework to underpin the tax policy

aspects of our review, we adhere to the following

principles of tax system design:

1. the function of taxes is primarily to raise

revenue to fund necessary and proper

government activity;

2. taxes should be efficient—raising revenue is

not a costless exercise, and the costs of tax

should always be considered and minimised;

3. the tax system should be neutral, so that it does

not distort people’s decisions;

4. the tax system should be fair—people should

be treated equally—and while compassion and

questions of need may influence tax design,

the more appropriate policy response may be

through government spending; and

5. the tax system should be simple so that

administration costs are low.

GROWING A HEALTHY ECONOMY

To understand the effect that taxes can have on

economic growth, we begin by considering what

factors drive growth. They can include:

1. value-adding infrastructure;

2. training and skills;

3. lower personal income taxes; and

4. good regulatory policies.

Another particularly important issue for New

Zealand is our need to increase productivity growth.

In 2008, the Treasury published analysis that showed

New Zealand was ranked 22 nd out of 30 countries

in terms of GDP per hour worked, as well as GDP

per capita. 8 We need to think about how to get the

most output out of every hour each New Zealand

worker works and the most value out of our natural

resources, every good or service we produce and our

intellectual property. 9

The Treasury has identified five inter-related

drivers of productivity growth: 10

1. innovation—including new ideas and new ways

of producing goods and services;

2. investment—including the formation of

finance;

3. enterprise—including the role of business in

expanding the economy;

4. skills—including more and better education and

training for both children and adults; and

5. natural resources—including getting more

value out of our land, water and raw minerals.

Tax policy can affect each of these drivers of

growth and productivity growth. For example, income

taxes can affect incentives for entrepreneurship,

by changing the level of reward that the risk of

innovation might bring. As entrepreneurs create

new products and opportunities, they are very

valuable to the economy—we need a tax system

that does not overly penalise or discourage their

important work.

HOW TAXES AFFECT OUR LIVES AND OUR

PROSPERITY

Researchers have found that some taxes are less

growth-inhibiting than others, because of their

vi

Lifting the Bucket: Tax policy and economic growth

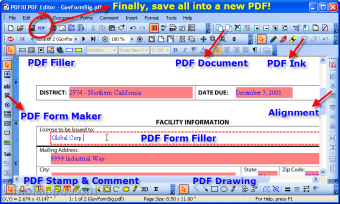

Figure 1. Effects of taxes and public spending on GDP growth

Taxes

Public Spending

Infrastructure

Education

Health

Growth Effect

Social welfare

Property

Consumption

Deficits

Personal

Corporate

Source: The Treasury, “Medium Term Tax Policy Challenges and Opportunities” (Wellington: 2009), 7.

differing impacts on the things that drive productivity

and economic growth. This paper considers the

effects on growth of consumption taxes, like our

Goods and Services Tax (GST), property taxes,

personal income taxes, and corporate taxes. It

finds that each type of tax has its strengths and

weaknesses—there is no such thing as a perfect tax.

Overall, however, the least growth-friendly taxes are

personal and corporate income taxes—the taxes

on which the government most heavily relies. By

contrast, consumption taxes are likely to be the most

growth-friendly, with property taxes also rated highly

(figure 1).

This suggests that changing where we collect

our tax from—as well as reducing the level of tax—

could make a genuine difference to New Zealand’s

growth performance.

THE LINK BETWEEN TAXATION, GOVERNMENT

SPENDING AND PROSPERITY

The way government spends money and the amount

it spends can also make a difference to growth.

We need the government to spend some money

to perform its proper functions, such as maintaining

law and order and providing a social safety net. But

if government gets too big, and steps into parts of

our common life that are beyond its proper role,

economic growth is overly restricted. As Treasury

Secretary, John Whitehead, has said, “Every dollar

that is spent by the public sector is a dollar that

is not spent on business investment, or left in

taxpayers’ pockets, or saved.” 11

Of course, not all government spending is bad

for growth. Within what is proper for a government

to do, we find that if a government spends more on

nominally “productive” activities, such as building

valuable infrastructure, there is a good chance

that growth will be positively affected. Whether

government spending is financed by distortionary

taxes (like income taxes) or non-distortionary taxes

(like consumption taxes) and whether the money

is coming from deficits or surpluses also makes a

difference.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Drawing on the insights of our literature reviews,

the principles of tax design, and a realism about

New Zealand’s current situation, we believe that

New Zealand needs to make some changes to the

tax system over the medium term for the sake of

our future. We must move towards a more growthenhancing

mix of taxes as a base, keep spending to

a contained level, and remove particular wasteful

tax incentives that are currently in the system. The

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

vii

following policy recommendations are indicated: 12

1. Personal income taxes

To make New Zealand’s personal income taxes flatter

and simpler over the medium-term, we recommend

that a two-step progressive rate structure should be

introduced, where:

• the top marginal personal income tax rate is

approximately 27%; and

• a low income tax rate is retained for taxpayers

who earn up to a threshold set according to a

relative measure of low income.

We do not recommend that a tax-free threshold

should be introduced.

We do not recommend that income splitting for

families should be introduced.

2. Corporate taxes

To lower the corporate tax rate, we recommend

that:

• the 30% rate should be reduced and aligned

with personal income and trustee rates at

approximately 27% over the medium-term; and

• the corporate tax rate should be further reduced

if the top marginal personal income tax rate is

also reduced over the medium-term.

3. Savings and investment taxes

We recommend that:

• the trust tax rate should be lowered from 33%

to align with the personal income and corporate

tax rate over the medium-term;

• the PIE tax rate should align with personal

income, corporate and trustee tax rates over the

medium-term; and

• KiwiSaver tax incentives for employers and

employees should be removed over the mediumterm.

4. Property taxes

We do not recommend that a land tax should be

introduced in the medium-term.

We do not recommend that a capital gains tax

should be introduced.

We do not recommend that a capital income tax

should be introduced.

5. Consumption taxes

We recommend that the GST rate should be increased

from 12.5% to 15% over the medium-term.

6. Size of government and government

spending

To reduce government size and spending we

recommend that over the medium-term:

• an upper limit benchmark for central government

operating spending could be set at, for

example, 30% of GDP; and

• accordingly, a benchmark for the size of core

government expenditure and provision of a

social welfare safety net could both be set at

around 15% of GDP.

To improve the quality of government spending,

we recommend that the government should be

mindful of the evidence relating to the composition,

financing and value of that spending.

WHAT’S RIGHT IS NOT ALWAYS POPULAR

While these changes are important, our research has

found that, by and large, they are not particularly

popular.

MaximInstitute commissioned UMR Research

to carry out a telephone survey of a representative

sample of 750 New Zealanders aged 18 and over to

see what their opinion was of a variety of tax policy

and government spending issues that are discussed

in this paper. The results of New Zealanders’ opinion

of tax policy issues, with a margin of error of +/-

3.6%, were that:

• 56% of participants oppose increasing GST,

if personal income taxes were lowered at the

same time; and

• 62% of participants oppose an annual tax

being charged on the value of land, if personal

income taxes were lowered at the same time.

The results of New Zealanders’ opinion of government

viii

Lifting the Bucket: Tax policy and economic growth

spending issues, with a margin of error of +/- 3.6%,

were that:

• 50% of participants think the government

should spend about the same as it presently

spends on KiwiSaver incentives;

• 47% of participants think the government

should spend about the same as it presently

spends on New Zealand Superannuation;

• 47% of participants also think the government

should spend about the same as it presently

spends on “20 hours free” early childhood

education;

• 46% of participants think the government

should spend about the same as it presently

spends on Working for Families; and

8

9

Where to Next” tax policy colloquium, Victoria University, 11

to 13 February (2009), 2.

The Treasury, “Briefing to the Incoming Minister of Finance.

Medium-term economic challenges” (Wellington: 2008), 5;

The Treasury, “Putting Productivity First,” Productivity Paper,

08/01 (Wellington: 2008), 4.

The Treasury, “Putting Productivity First,” 1.

10 The Treasury, “Briefing to the Incoming Minister of Finance.

Economic and fiscal strategy - responding to your priorities”

(Wellington: 2008), 3-4; The Treasury, Productivity Papers

Series (Wellington: 2008), http://www.treasury.govt.nz/

publications/research-policy/tprp.

11

J. Whitehead, “Public Sector Performance.” Speech to the

Victoria University School of Government seminar, Renouf

Foyer, Michael Fowler Centre, Wellington, 20 July (Wellington:

The Treasury, 2009), 4.

12 Note that as they are not costed, they are introductory only.

Final recommendations and costings will be presented in the

final paper of this series.

• 48% of participants think the government

should spend about the same as it presently

spends on interest free student loans.

Despite the fact that the changes we recommend

may not be popular now, they remain important

and not only justified but crucial. While the

government must pay careful attention to what

its constituents would like, it is also charged

with the responsibility to do what is best for the

country as a whole. The government must convincingly

explain why the changes are required.

Given the outlook of our economy and future

pressures on government spending, it seems that the

design of the tax system needs to be reconsidered.

If we neglect this responsibility we face serious

consequences in the long-term.

ENDNOTES

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

R. Langworth, Churchill by Himself: The definitive collection

of quotations (New York: Public Affairs, 2008).

The Treasury, “Challenges and Choices. New Zealand’s Longterm

Fiscal Statement” (Wellington: 2009).

The Treasury, “Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update”

(Wellington: 2009), 33.

The Treasury, “Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update,” 33.

See the core Crown expenses tables in The Treasury, “Half Year

Economic and Fiscal Update,” 119ff.

Cf. The Treasury, “Challenges and Choices. New Zealand’s

Long-term Fiscal Statement,” 9-10.

M. Benge and D. Holland, “Company Taxation in New

Zealand.” Paper presented to the “New Zealand Tax Reform -

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

ix

This page has been

intentionally left blank

for publishing purposes

x

Lifting the Bucket: Tax policy and economic growth

SECTION 1

Introduction

Taxes are an integral part of our society and our

economy, funding government to do what we need

it to do. However, the health of New Zealand’s tax

system is currently under threat. 1 Once a model

to other countries of a relatively efficient system

which did not unduly discriminate against people’s

choices to work, invest or start a business, the past

decade has seen many new distortions introduced

which threaten to undermine the tax system’s

efficiency and capacity to collect revenue. 2 The

previous government decided to tax the highest

income earners at a higher rate, raising the top

marginal personal income tax rate from 33% to 39%.

This allowed significant gaps to emerge among tax

rates on different bases, such as personal, corporate

and trust income. Rather than boosting the amount

of tax collected, over time this kind of policy can

create loopholes that lower the tax take, 3 and can

produce all sorts of unintended consequences,

such as lower rates of workforce participation and

business creation.

Taxes can change our incentives—that is, how

much we do or value certain things, like working

or leisure. Government policies like KiwiSaver and

changes to Portfolio Investment Entity (PIE) rules

distort our incentives for saving and investment, 4

while the Working for Families package has altered

incentives to work harder, or longer, for more pay.

Working for Families has also introduced corrosive

effective marginal tax rates on certain families’

income. 5 Together, these sorts of policies have made

the tax system more costly to administer and have

increased compliance costs, thereby raising the costs

of collecting tax. Besides this, government size and

spending has been on the rise, such that government

spending was recently equivalent to over a third of

the value of what we produce. 6 All of this works to

undermine New Zealanders’ living standards, as tax

inefficiencies and perverse incentives chip away at

or inhibit what our nation produces.

In 2009, the New Zealand Government

established a Tax Working Group to identify major

issues the Government should consider with

“medium-term tax policy and to better inform

public debate.” 7 The Group considered these sorts of

mounting problems with the tax system and reported

back in January 2010 with a range of suggestions

for restoring the tax system’s fairness and revenueraising

integrity. It recommended options such as:

aligning personal income, corporate and trust tax

rates; increasing the rate of Goods and Services

Tax (GST); and changing the way property is taxed,

for example by closing loopholes on residential

rental property. 8 While the Tax Working Group’s

recommendations are important and should be duly

considered by the Government, the Group’s brief

restricted it to considering only tax changes that are

“fiscally neutral”: that is, ones that would not reduce

the total amount of tax the government collects.

The Group’s recommendations must be seen

within this constraint; it was not able to consider

how the total tax burden could be lowered

by reducing government spending. Government

operating spending (that is, core Crown expenditure)

was 29% of gross domestic product (GDP) as

recently as 2004. 9 It is now about 36% of GDP, partly

due to pressures on the Government to provide

greater assistance during and after the recession,

such as income support, and to the recession’s

effect on GDP itself. 10 However, the recession’s

impact should not distract us from how operating

spending as a share of GDP still tracked up between

2004 and 2008. 11 If New Zealand reduced government

spending, more significant change to the tax

SECTION 1 | Introduction 1

system would be possible. This could alleviate the

total tax burden New Zealanders face, thereby

stimulating the economy and improving living

standards.

The focus of this paper

In light of this, the purpose of this discussion paper

is to consider some of the economic questions

affecting our tax system—primarily, questions about

how taxes affect economic growth. It is the third in

a series that seeks to join up theory about the role

of government and community, the meaning and

enacting of justice, compassion and freedom, and

the economic literature on taxation. The goal of the

series is concrete policy recommendations based on

this holistic framework.

We believe the relationship between taxes, the

economy and society is important because the way

taxes affect the economy also affects people’s living

standards and the opportunities open to them in

life. Of course other economic issues, such as New

Zealand’s indebtedness, also have an impact on New

Zealanders’ livelihoods—and tax can have an impact,

even if indirectly, on these sorts of issues. However,

to cover all of the possible ways taxation could

interact with the economy would be difficult and,

moreover, hard to describe with certainty.

We draw on recent work by the Organisation

for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

and others that looks at how taxation interacts

with various economic growth drivers—for

example, innovation and investment—as a way of

understanding how taxation influences a country’s

economic performance. 12 This body of research has

implications for how governments may choose to

collect and spend taxpayers’ money.

We have chosen to limit our discussion’s scope

to concentrate on taxes that are primarily designed

to be revenue-raising—such as personal income

taxes, consumption taxes like the GST and corporate

taxes—and on the way government spends the

money raised by taxation. 13 These taxes are also very

important because they make up the greatest share

of all the taxes New Zealanders pay. 14

We also recognise that governments may

collect revenue through corrective taxes, such as

environmental taxes and “sin” taxes, like those on

tobacco. Since all taxes impose a cost, the idea is

that corrective taxes can be used to make people

do less of what is harmful to society as a whole, for

example taxing fuel emissions to reduce pollution.

Corrective taxes are important and will have an

impact on economic growth, but these taxes should

be assessed on a different set of criteria to revenueraising

taxes because the main purpose of corrective

taxes is to change people’s behaviour and not to

collect government revenue. We therefore do not

discuss corrective taxes in this paper, as their policy

underpinnings and purposes are quite different.

Our approach is situated within a comprehensive

income tax framework. The theory of comprehensive

income taxation suggests that governments should

endeavour to tax all income; that is, a dollar earned

should be a dollar taxed. 15 The wider the sources of

tax—the tax base—the more tax can be collected

from the myriad ways people earn an income. The

tax policy framework New Zealand adopted after

1984 was a comprehensive income tax approach, 16

which improved the tax system’s fairness and

integrity. This approach can help ensure the design of

the tax system satisfies horizontal equity concerns,

meaning that all taxpayers who are in the same

welfare situation are treated in the same way.

That said, we recognise that the comprehensive

income tax approach is just one tax policy

framework. Another, optimal tax theory, suggests

government should ideally tax what we take from

the economy (consumption) and not what we put

into it (income). 17 Among other things, it is thought

that taxing consumption should help stimulate the

formation and productive use of capital throughout

the economy. Optimal taxation theory, therefore,

challenges the idea that we should tax all income

sources in the same way, since it suggests, for

example, that capital and savings should be more

lightly taxed than other income, 18 because of their

role in driving economic growth.

While optimal tax theory makes worthy

suggestions about how taxes might be designed in

theory, an optimal tax system would be difficult to

implement in practice because, for example, it would

require policy-makers to have accurate, up-todate

information about taxpayers’ preferences that

simply is not available all the time. An optimal

tax system would also require more complex tax

structures, 19 which would mean differentiating

clearly between forms of capital and labour income

so that different tax bases could be taxed at

an optimal rate. For these reasons, we have not

2

Lifting the Bucket: Tax policy and economic growth

followed an optimal tax approach, instead relying on

a comprehensive income tax system which is likely

to be simpler to administer and easier for everyone

to understand.

A comprehensive income tax framework

suggests the tax system should be designed with

a policy of lowering and flattening tax rates and

broadening the tax base. This does not mean we

necessarily believe that every income source should

be taxed. The extent of the tax base should also

be determined by whether a tax on a particular

source is fair, poses implications for economic

performance, and/or is simple to administer. We

therefore believe many of the efficiency and

growth objectives held as important by optimal tax

theory can still be achieved within a comprehensive

income tax framework so long as government

considers the implications of taxing each income

source. This means our discussion and our policy

recom-mendations are presented within a modified

comprehensive income tax framework.

Although we are concerned with how taxes

affect economic growth, we do not suggest

economic growth is an end in itself, crucial and

valuable as it is for improving people’s lives. We

suggest whatever policy direction is chosen should

also take account of other considerations of

people’s non-material well-being—we need what

has been called a “functional economy.”

A “FUNCTIONAL ECONOMY”

Building on an established philosophical tradition,

the economist Bernard Dempsey further developed

the idea of a “functional economy.” 20 The theory of

a functional economy suggests that the economy

does not exist apart from society and people. Like a

human person, the economy should have a reference

point for its operation. Simplifying Dempsey’s

thought to its core, he believed the common good,

defined in terms of social (commutative) justice, was

this reference point to which the economy should

be oriented.

We can think of the common good as what is

good for sustaining holistic, social life. Since human

beings are relational, genuine fulfilment in life

comes from living in community. Community and

the common good are in some ways inseparable. 21

Some theorists have argued that what is good for

sustaining life is indicated by intrinsically basic

goods that we all share or partake in, like life,

knowledge, friendship and play. 22 These basic goods

are good for all people at all times and in all places.

This means that the common good is revealed by

reason and by the customs and traditions that have

shown themselves to sustain the basic goods of life. 23

The common good is not a simple end goal that

can theoretically be achieved once and for all—like

eliminating poverty or income inequality—it is

something “valued, supported and protected by

society’s members” for their benefit and flourishing

as people. 24

Dempsey suggests that the overriding purpose

of economic exchange is not simply to produce

wealth. His position implies that economic exchange

has a clear social dimension. Work, for example, is

not merely a way to generate income; it also helps

to develop the human person. 25

Similarly, businesses, and in particular

entrepreneurs, 26 should not be seen as solely

engaged in commerce, but rather as using

their intelligence and freedom to create

opportunities for all of us to enjoy better

lives by generating wealth, and creating jobs

and opportunities for investment. Businesses

also “form communities of work in which investors

and employees can use their resources, their talents

and their energies to support human well-being.” 27

They also contribute to the common good themselves

by creating wealth, providing good work for

people and being wise stewards of the community’s

resources. The broader part that business plays in

society means that we should not downplay the

importance of wealth creation and its source in

human ingenuity and work. 28

Seen in this way, work, businesses and

entrepreneurship fulfil larger human purposes, and

should be valued accordingly. We believe the same

is true of the economy and of economic growth.

That is, while economic growth is not an end in

itself, we should value it because it can help us

realise the ends indicated by the common good,

for true human flourishing. The common good as

a reference point can also serve to restrain what

might otherwise be excesses of market participants

or a pursuit of economic growth at all costs.

Nevertheless, free markets produce the wealth that

sustains a community in the most efficient way,

and reward human initiative, ingenuity, industry and

self-discipline.

SECTION 1 | Introduction 3

MEASURING WEALTH AND WELL-BEING

If you were to ask most economists how we could

measure whether people were better or worse off

in various countries, they would probably reply

that a reliable way of doing this is to first consider

a country’s GDP, GDP growth and GDP per head.

They are considered key measures of a country’s

economic performance since they are the best

available economy-wide measures of production

and income—two crucial factors behind better

living standards. Though recently the value of GDP

as an indicator of a country’s well-being has been

called into question, 29 GDP growth remains a

very important and useful indicator despite its

limitations.

GDP per capita as a well-being measure

An indicator that economists and governments

often use to consider whether a country’s economy

is growing or not is to look at the change in GDP

per capita. Statistics New Zealand defines GDP as

“the total of goods and services produced in New

Zealand at market value after deducting the

cost of goods and services used in the process of

production,” 30 before depreciation deductions. GDP

therefore “describes in a single figure, and with no

double counting, all output or production carried

out by all enterprises, government and non-profit

institutions and households in New Zealand during

any given time.” 31 GDP growth is the rate of change

in per capita GDP (that is, the share of GDP per head

of population).

The OECD has recently discussed what GDP is

and what some limitations might be with using it to

assess well-being in and across countries. They say

GDP per capita “is the most commonly used measure

of material living standards because it is readily

available for a large number of countries on a timely

basis.” 32 Despite this, since GDP per capita measures

economic output, it misses some aspects that are

important for judging a country’s welfare, including

the value attached to leisure and the use of nonrenewable

resources. 33 For example, in the OECD’s

opinion it would be more accurate to measure living

0 thoughts to “Maxim free download pdf”